There are a few things I like to do with my spare time. Obviously there’s writing, and with writing comes reading, because you can’t be a decent writer without being interested in reading. When I have the money and time I like to travel and make a fool of myself taking pictures of a little blue pig in places of interest. I like to cook when I can (a product of travelling, really) and I play music too, in fact the degree I’m studying is in music technology, but there’s one thing I’ve been doing longer than any of these: gaming, and video gaming in particular. I started young with a sega master system playing games like shinobi and the (really bad) master system version of sonic the hedgehog, and it just carried on from there, really (I should point out that despite my features making it seem otherwise I was born in the late 80’s, so I missed all the old British consoles like the Sinclair Spectrum and that era of gaming). Sonic was my hero as a kid, I played the games, watched the cartoons, read the comics, I’ve still got a Sonic teddy up on the top of my bookshelf. But that was back when games were simple things, and, more importantly, seen as the hobby of geeks or children. That isn’t to say those games are lesser, in fact I still play a lot of those mid-90’s games now.

These days, you could say the gaming industry is a little different. Major games can now cost millions to develop, the audience has exploded in size and we now see fewer and fewer decent games developed in the vein of Sonic the hedgehog and Super Mario. Games have grown up alongside us, they provide more now; more visual stimulation, better sound effects, better music, characters and plotlines we can absorb and relate to. The closest thing you can compare modern gaming and the gaming industry to is cinema. They’re the next step up, it’s active cinema: you are part of what’s happening on the screen, you have a say in how it goes, and it’s for that very reason that the gaming industry is worth billions. Like the movie industry though it has its flaws. The big-name developers with their monster budgets dominate the commercial scene and they’re unlikely to take big risks. They all have their own little niches but there’s more than a hint of mainstream games becoming a little formulaic. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, just as there’s nothing wrong in watching the last Rambo film even though a blind, deaf cat would know exactly what’s going to happen. It’s fun! There’s no problem with reading Stephen King*, but sometimes it’s nice to read Kafka, or Tolstoy.

And that’s where indie gaming comes in. With the power of modern PC’s and the knowledge of programming, games made by small groups of people are developing a thriving underground scene of unique games. Not having to meet sales targets or satisfy shareholders means the imagination of the developers can run wild. Like amateur and independent films, these games don’t always have the sharp production style and visual appeal of their mainstream counterparts but they can touch on themes and elements on gameplay that the big boys just wouldn’t attempt to. Here are a few I’ve come across recently. I should point out that I’m not going to deal with the indie games that are really big, like minecraft or terraria, rather I’m going to concentrate on the indie games that are more underground.

First off, let’s get the elephant in the room out of the way: Dwarf Fortress. DF is a game that is an oxymoron, essentially: it is infinitely complex, meticulously detailed, yet it looks like a game someone made in their basement in the 80’s. The objective of the main mode of the game is to build a fortress in the mountains for your dwarves and watch it grow, thrive, then fail and fall apart, and it will fail. The game’s unofficial motto is ‘losing is fun’ and you will lose a lot. A simple way of losing could be running out of food (and watching your dwarves resort to chasing after vermin in the fort in their last desperate throes) but there are all kinds of way for things to go downhill. Goblins could lay siege to your fortress or ambush your lumberjacks as they work away in the forests, or maybe there’s something darker and more evil in the very ground below you. Who knows! I really can’t say because every game is unique, and by that I mean completely unique. Before you can start playing the game needs to generate a world for your dwarves to live in. You set the parameters for this but no matter what you designate the game will create an entire planet, complete with a history of the world with historic figures, civilisations, ancient creatures and events which will all tie in to your own game as your masons carve images of famous battles into the walls and leatherworkers sew their images.

The welcome screen, setting a visual standard

The entrance to my current fortress, with a trade depot and ballista defences

The entrance to my current fortress, with a trade depot and ballista defences

Here’s the kicker though: you have to use your imagination. As I mentioned, this game looks like it was made in the 1980’s. It’s basic, crude even, compared to looking at ‘the matrix’ as, in time, a bunch of symbols begin to represent an entire world. You’ll find text descriptions of practically every character and item in your game, so it really is down to you and your imagination to make something of all this. I hear the whole imagination thing has worked out well for books down the years though, so don’t be scared away by this. You should also try and not be scared by the game’s infamous learning curve. There are plenty of tutorials out there in the blogosphere and on youtube that will help you find your feet, and once you’re making progress you’ll find yourself completely engrossed in one of the most incredible games ever created. Oh, did I say created? Even though the gameplay is ‘complete’ and you can play indefinitely, the game itself is only a third complete. When you grasp how big the game is now and imagine how it’s going to be when it’s more than twice as large you’ll see just why this game is the biggest thing in the underground gaming world. Oh, and this whole game is being programmed by one man on his own, funded purely by donations by people who’ve enjoyed the free-to-download game. No marketing, no need to pay any money to play the game at all, yet this game has raised enough in donations for Tarn, the programmer, to give up his job and work on this solely.

Next up is something of an honourable mention, really, because it’s pretty hard to find these days. It was a labour of love over eight years by a team of programmers and artists who did it all for free (and released the game for free) only for them to receive threats of legal action and have to pull it within days of its launch. It’s called Streets of Rage Remake, and answers the cries of so many fans of the old sega game by combining all of the old games along with adding a few new features. You could use characters from one game (and a few of the boss characters) in the levels of another, new weapons and levels were designed and added, just simple, good old-school fun. Obviously though Sega weren’t too happy at the thought of people taking their property and redesigning parts of it and shut the whole thing down hastily, but if you do a little searching you just might be able to find someone hosting the zip file for download. You didn’t hear that from me, though.

Kicking ass and chewing bubblegum, except I'm all out of gum.

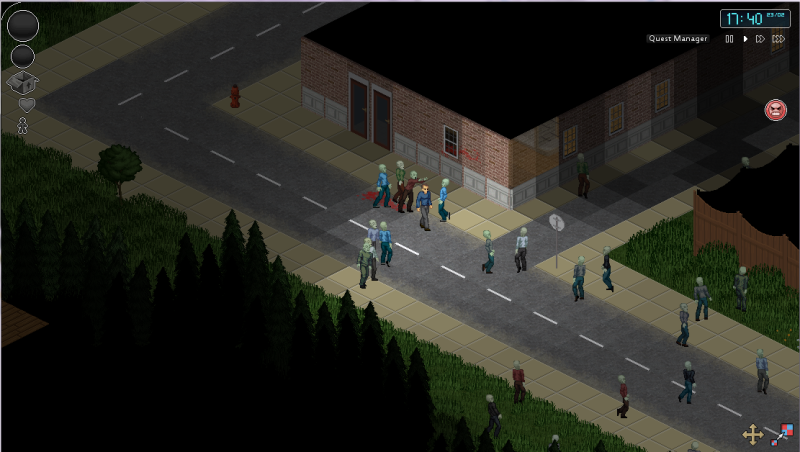

Last but not least is a game that I’ve only stumbled across recently by accident. It’s called project zomboid, and it’s a zombie survival game. Plenty of those around, sure, but not in the style of this game.

Raiding a grocery store

It’s viewed in a traditional 2D isometric style, but that’s not too uncommon for indie games. The big difference is this game takes much more inspiration from traditional zombie films than action games like left4dead. Like Dwarf Fortress, this is a game where you’re going to lose. The opening line of the game is ‘this is how you died’, it works around the concept of telling the story of your death rather than giving some glimmer of hope of somehow ‘winning’ the game. Just like in the flicks, if you get scratched by the zombies you might get away with it, but if you’re bitten that’s it, you’re infected and there’s no hope of a cure, so you might as well grab whatever weapon you have, step outside, and try to take as many of the bastards down with you. It’s vital that you find a building and fortify it, make it your safe house with barricaded doors and windows (because if the zombies can see inside they can see you). You’ll need to eat, which means leaving your ‘fort’ and raiding stores or houses, but you have to keep your wits about you and not make too much noise or you’ll attract the attention of the undead. A single zombie, you should be able to handle without any real trouble, but some zombies are slower than others, and the movements of one zombie can influence another. You might think you’ve sneaked away without event but you may wake up that night to hear a horde of 100+ zombies trying to break down your door.

Uh-Oh

Like Dwarf Fortress, Project Zomboid is a game still in progress but is very playable. Unlike DF, this game is using a unique funding arrangement that may become more and more common in indie gaming. Gamers buy a licence for Project Zomboid and receive a login. They can then download the unfinished game and use this login to play it, with the game being updated as time goes on. The price of the current version of the game is a very cheap £5 as a mark of appreciation for the commitment these early gamers are showing, but as time goes on this price will go up for new gamers (the final price hasn’t been announced). This is the biggest advantage of the indie scene: it’s a community. Project Zomboid has dedicated forums where indie gamers, whether they’ve paid into the game’s funding scheme or not, can talk about the game, what they like or don’t like, and what they’d like added to the game in the future. They have a say as to how this all works out and whilst there are always nay-sayers the general feeling is that of goodwill, especially evident after the PZ team’s office was burgled just recently. I think, rather than try and think of something sharp and thoughtful to end on, I’ll finish with a video. Keep in mind these guys raised more than double their donation target before the deadline; I think that speaks volumes for indie gaming as a whole.

*This is 100% OK to say because Stephen King himself says his books are just pulp fiction or as he put it ‘my books are the literary equivalent of a big mac’